Hello,

After a longer pause, the June newsletter is here. I hope you've been enjoying the start of summer and the gift of long evenings. This month, cherries and storms are my favorites, along with the anticipation of things to come. June feels like a promise – the moment before the first kiss.

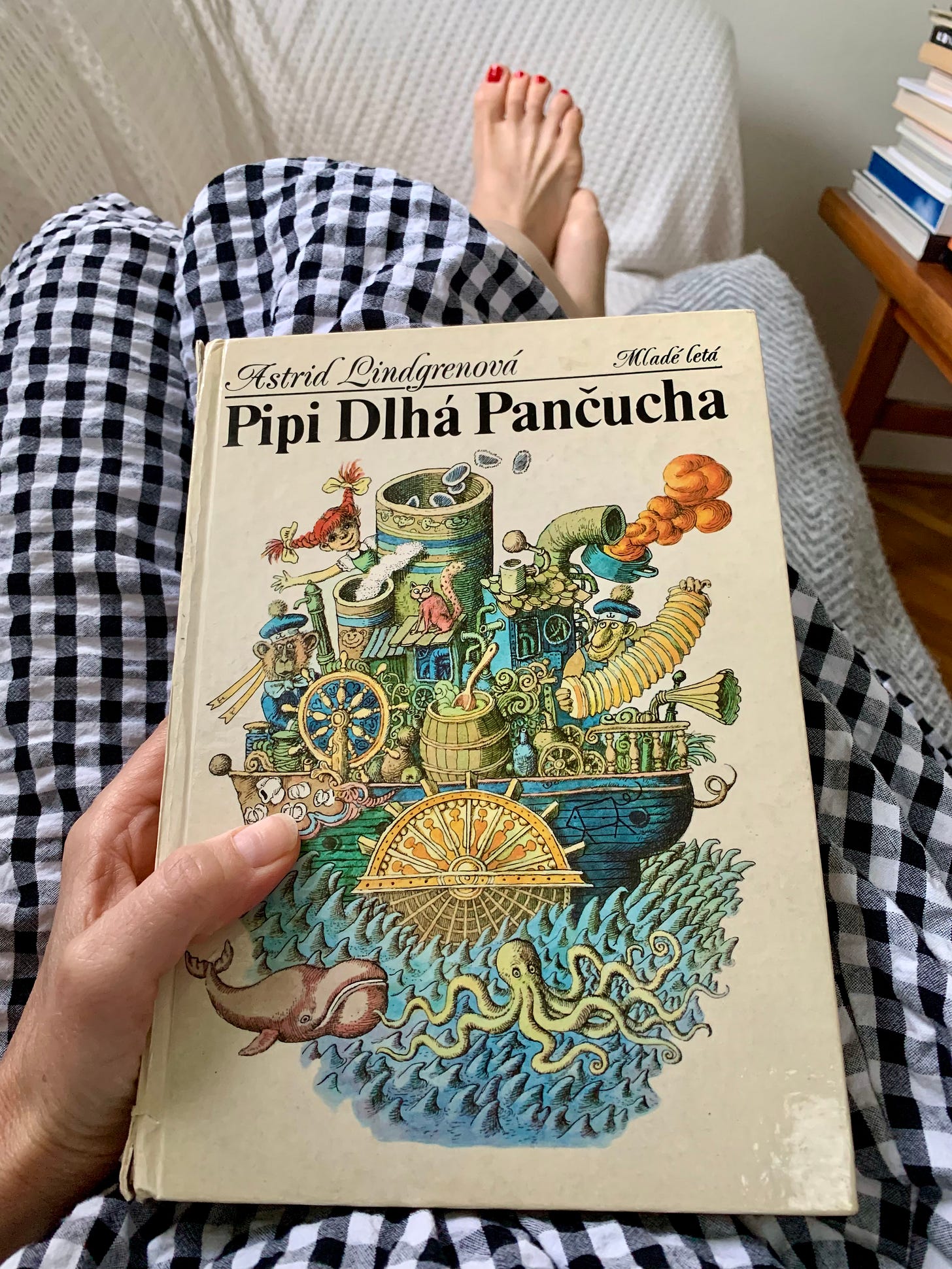

This year, I’m dedicating each month's newsletter to a different topic. So far, I’ve written about home, patience, flaneuring, spring, and strangers. Today’s letter is a bit different, but maybe not! I believe Pippi Longstocking is more than just a character; she’s a phenomenon, an institution – a category of her own.

Along with my other adult female heroes, she continues to resonate within me, her influence ever-present. Since the early 90s, Pippi has lived inside me, lending me her strength, even when I’m unaware.

I don't know about your relationship with her, but I believe you'll enjoy the read.

Happy summer,

Katarina

On Pippi Longstocking

She was a companion who, albeit fictional, felt as close as a dear friend. I can’t recall the first moment held that book in my hands, but I vividly remember it was the very first book that made me realize – or perhaps intuit – that reading could be an occasion. And just like every special occasion, it should be given its own sacred time and space, a parlor.

Reading Pippi Longstocking soon took on the characteristics of a ritual. In our living room, I’d push two armchairs together to form a ‘boat’. Once seated inside, I was ready to dive into Pippi’s thrilling adventures. The two armchairs and the Persian carpet (the sea) underneath created a buffer between Pippi’s fantastic world and the reality of our grey block and my little hometown. In this make-believe boat, Pippi could crawl out of the pages and make me question the limits of (im)possible.

I can't count how many times I re-read the book. At first, I read it chronologically; later, I'd open it to a random page. I knew each story as if I had lived it myself.

Pippi Moves into Villa Villekulla

Pippi Plays Tag with Some Policemen

Pippi Arranges a Picnic

Pippi Has a Birthday Party

I still have the same copy in my bookcase. Its author, Astrid Lindgren, sits on my cherished books shelf, among other 'underdogs' like Annie Ernaux, Rebecca Solnit, and Ocean Vuong. When I touch the pages now, they feel as soft as worn-out leather. Like well-worn shoes, the pages softened under my small fingers.

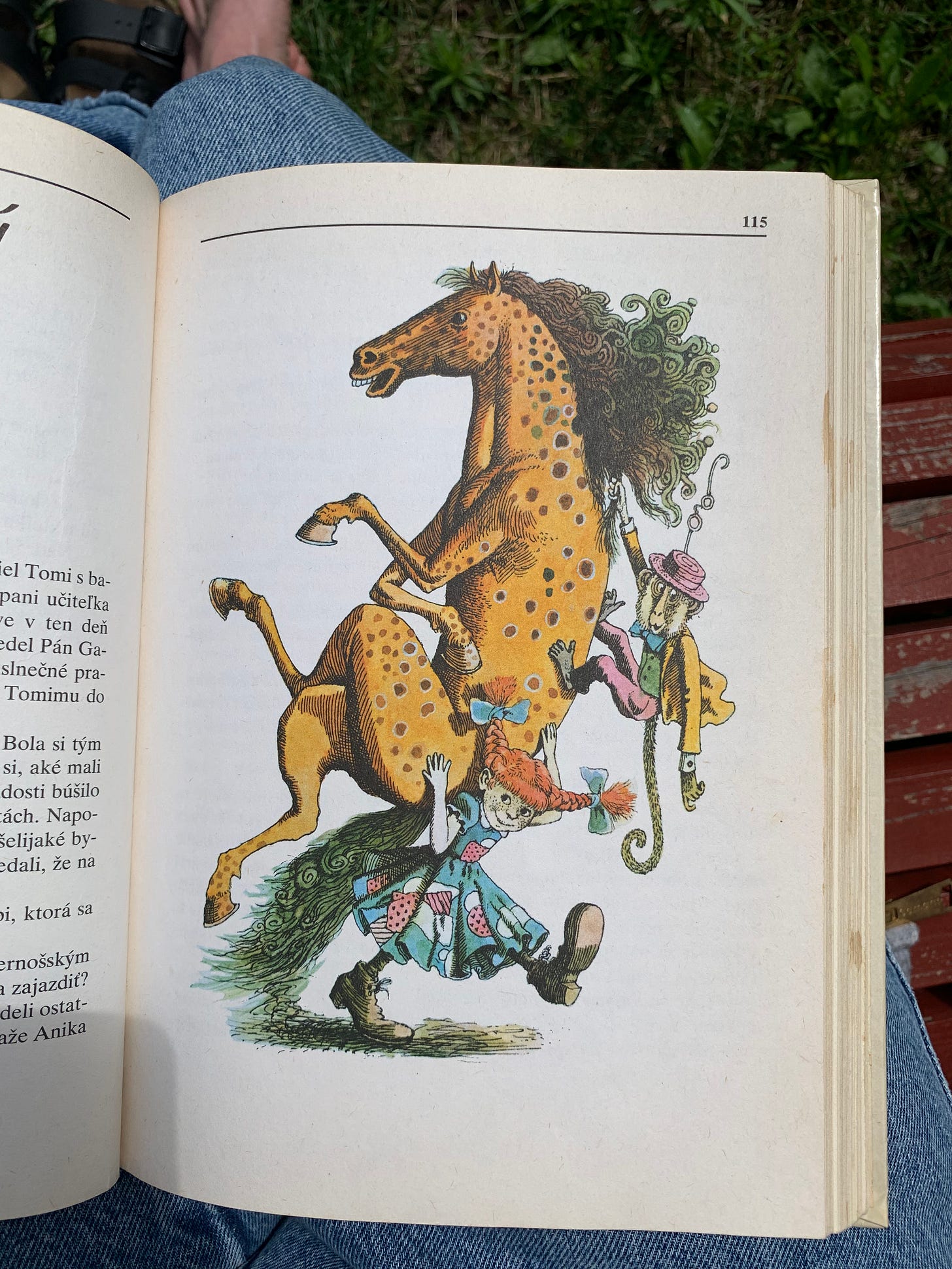

There’s no doubt Pippi was the first feminist I had encountered, even before I knew what that word meant. Published as early as 1945, Lindgren sent her Pippi out into the world to challenge societal norms in the most seductive and irresistible way. She was everything a ‘good girl’ was not supposed to be: messy, outspoken, loud, strong (so strong that she could lift a horse and so strong that she could bear living alone, and actually enjoy it). But alongside her disobedience, she had generosity and a heart so big it could fit in a horse. A true feminist indeed, akin to the filmmaker Agnes Varda, whose Parisian house was a real-life incarnation of Villa Villekula). Pippi ensured she had a good time no matter the occasion, and effortlessly lured others into her world, where her self-imposed rules had the elasticity of a rubber band, stretching and adjusting to her whims.

In childhood, Pippi accompanied me and stirred that adventurous, tomboy part of me that was hiding under the good girl I was trying to be. Many years—decades—later, I realized another aspect of our kinship that I couldn’t recognize as a child. Looking back, I understood that what drew me to Pippi’s world was that she made me feel seen and accepted. I was a child growing up without a father, who was somewhere ‘out there’, just like hers. Captain Ephraim Longstocking went missing at sea, only to turn up as king of a South Sea island. For some years, my mother would make up stories about the whereabouts of my father too.

However much I admired Pippi (whose full name was Pippilotta Delicatessa Windowshade Mackrelmint Efraim's Daughter Longstocking) for her cheekiness and bravery, and coolness, the undercurrent of our connection was that she felt like kin. She was a misfit and so was I, no matter how hard I tried to fit in the class with my good-girl-ness. The moment I pushed one armchair to the other and climbed inside my/our boat, I was at home. I felt safe, and certainly free, too. My life turned out alright—Pippi’s father lived on an exotic island, and mine had his own big family in a nearby village (although I had not known this yet).

The Pippi Longstocking book wasn’t new when it came to me. It was pre-owned and pre-touched, having originally belonged to a girl named Eva, who was the daughter of my mother’s best friend.

Just like Pippi, Eva later showed me that other worlds were possible. She was the one who initiated me into the depths of a creative process. Eva made me realize that art wasn’t just about making things—it was a way of thinking, of observing everything around me—a way of existing fully in the world and noticing the most subtle beauty on the cusp of visibility: a spiderweb in the dusk, specks of silvery dust shimmering on an old wooden table in the sunlight, the barely perceptible scents of fading summer, the life of sky, of flowers.

Seven years younger than her, I always sensed a subtle shift in reality when we spent afternoons together, whether we were working on something artsy or simply taking a walk. Being with her meant always being two feet above the ground, feeling elevated in my senses, just enough to grasp the magic that lingered within a heightened state of awareness. She showed me that I too could open myself up to things overlooked by others.

Just like Pippi with her oversized shoes and patchwork dress, Eva became my later ‘girl crush’ in terms of fashion. Looking back, I realize she was the first person I knew who possessed an innate sense of style—the kind that manifests in the subtlest choices combined to create a perfection that's hard to replicate. Her elegance always had a quirky touch.

When she moved to London in the early 2000s, she wore large midi skirts and neon sneakers, along with other garments I admired and thought only she could pull off, with her unique sense of ease. In our small hometown's conformist social scene, she was often seen as an outcast. Each time I saw her in a new outfit, I held my breath, feeling similarly breathless as when I flipped through the thick I-D magazines she brought me from London. This was before the Internet, and everything on those pages was an overwhelming, unsettling, yet strangely satisfying aesthetic indulgence.

Similar to Pippi, Eva was, in a sense, semi-fictional. I believe that, like Pippi, deep down she was also a loner. The fact that I was one too made our kinship firm within the seams of our friendship. I never spoke about what she meant to me—I was too young to verbalize my appreciation—but our bond grew deep under my skin. Even now, as I write these words, I can hear her voice. It always sounded enchanted when she was about to announce a small adventure, and I was always thrilled to participate.

I remember my mother often made fun of Eva, dismissing her as impractical for real life, more likely to admire imprints in flour dust on the floor than to bake a cake. Yet Eva loved food and was a good cook too. Many years later, in 2017, in the wee hours of the first spring day, when the light was as delicate as the things she cherished—porcelain, candles, waffles, dry leaves—she jumped from the balcony of her mother’s 7th-floor apartment.

Alongside Pippi, Eva still lives within me – in how I pay attention to things, and how I handle what I perceive.

***

Earlier this week I took my ‘bible’ from the special bookshelf and opened it to a random page. It turned out to be the chapter where Pippi invents a new word. When Pippi coined the term špunk, she had no idea what it was, but she knew exactly what it wasn't: a vacuum cleaner. Together with Tommy and Annika, they strolled through town, popping into various stores to inquire whether špunk was sold there. Clueless about špunk, most shop assistants pretended to be familiar with the thing, afraid to fail in performing adulthood. (I view this chapter as a perfect commentary on the facade of adulthood, that is in most cases feigned, and frequently overrated).

Thirty years later, as I re-read the špunk adventure, I'm struck by how vividly I recall Pippi's radical honesty and recklessness, yet I had nearly forgotten her capacity for radical imagination.

All maps are limited to marking distinct roads. What truly matters often lies beyond the official boundaries. Pippi Longstocking knew this. So did my friend Eva.

I close the book, throw on a hoodie, and walk down to the garden where I sit on a bench. In the veil of dusk, the bats emerge. Endowed with their sophisticated navigation system, they require no map of the visible world to sense what they need to sense. They flutter above my head in circles, their wings beating at a frequency that seems irrational to me, yet I recall that my logic is not the only one the world has shaped around. The way bats move aligns with a different reality, one beyond what is visible. I speculate they might understand what špunk is.

Eva, who chose to navigate her life by ignoring many rules, taught me that radical imagination is a magical tool. She showed me the expansiveness of the mind: there exist worlds in between what we have words for. Like Pippi, she offered me a map where the paths are not logical, yet thrilling. Naturally, such a map can also be challenging. Yet I never desired a different one.

Later, I learned about radical imagination from other women. Agnes Varda, who, as a new mother who still wanted to continue working, used limits as prompts and shot her film Daguerréotypes, documenting the everyday lives of the people and shopkeepers on Rue Daguerre, just outside her door. Equipped with her camera powered by an extension cord plugged into her home, she did magic within a creative radius of just 90 meters. There are others: Clarice Lispector, Clarissa-Pinkola Estes, Claire-Louise Bennett. My close friend and collaborator, also named Eva, who excitedly keeps teaching me what can be discovered on the map bereft of reliable but boring roads.

Radical imagination is a tool we can reach for when we come to the end of the known path: getting lost in a foreign city, the realm of grief, of heartbreak, of…

When I gaze upon this image of Pippi carrying a horse now, I realize her feat wasn't solely due to physical strength. It’s about envisioning that the weight of the burden can be shared between the now and what will come tomorrow, between real and potential, between what’s in our control and what’s beyond it. Pippi’s strength lay in her radical imagination. That’s why she had no reason to be afraid.

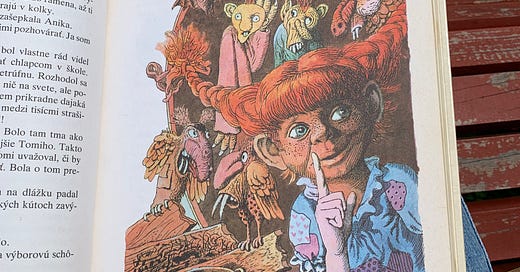

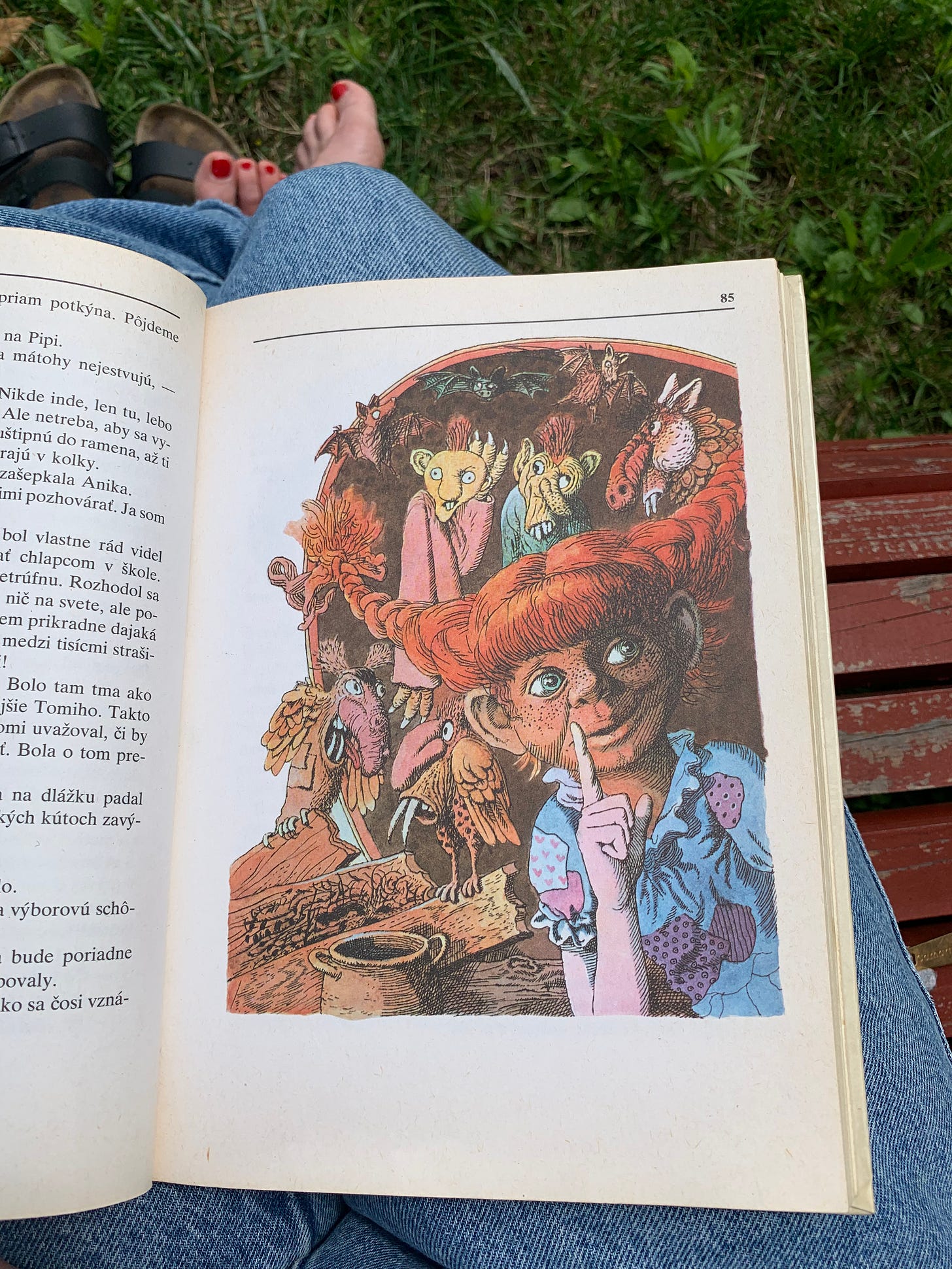

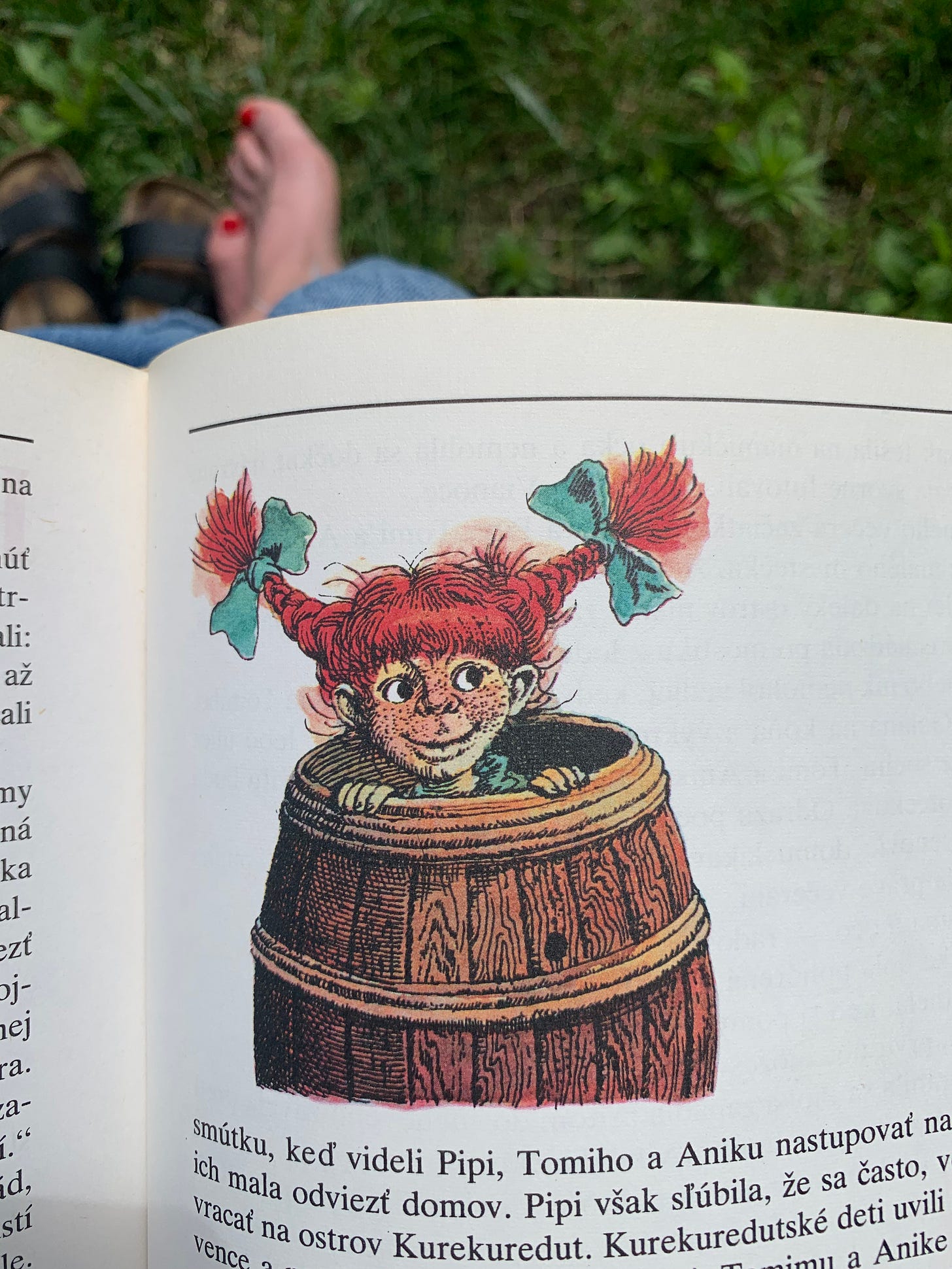

(The illustrations featured in this letter were created by Slovak artist Peter Kľúčik, whose incredibly vivid and perfectly surreal interpretation of Pippi’s world from 1985 profoundly influenced my generation of kids and those that followed. For us, no other depiction of Pippi is acceptable.)